Even before the coronavirus rocked our lives and our economy and put the spotlight on the heroic people working on the front lines of the healthcare and food industries, a change was stirring in corporate boardrooms and C-suites across the globe. The concept of making business decisions based on their effects on the lives of employees, suppliers, customers and communities, rather than solely on the company’s financial bottom line — is referred to as “stakeholder capitalism” — a concept has been part of Hormel’s DNA since its founding.

Three years ago BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, challenged the more than 7,000 firms in its investment portfolio to re-engineer their long-term strategic plans with the goal to improve all of the lives impacted by their companies, not just the bank accounts of their investors. The following year, the Business Roundtable, comprising the CEOs of hundreds of America’s largest companies, announced that it had revised the organization’s statement on the “Purpose of a Corporation.” It switched from focusing on enriching shareholders to a broader, more holistic focus on well-being and prosperity for all of a corporation’s stakeholders, including customers, employees and communities — a dramatic about-face.

More than eight decades before the Business Roundtable’s declaration, Hormel Foods was hard at work redefining the purpose of the corporation. George Hormel knew from first-hand experience that advances in technology were unlocking new levels of efficiency. He personally spearheaded many of the innovations in food processing and packaging that propelled his company’s growth from a 3-person Austin meat seller in 1891 to a 4,000-employee enterprise in 1934 feeding millions of Americans. But equal to his passion for innovation was his empathy for the people who worked for his company. Rather than regarding technology purely as a cost-saving investment, George and his son Jay worked hard to apply technology as a means of increasing overall prosperity.

As we recover from the pandemic’s destructive effects on the national and global economies, we need look no further than Austin, Minnesota to find a successful blueprint for navigating a crisis not unlike this one. While Hormel Foods has weathered natural and man-made threats to its existence since its founding in 1891 — financial crises, famine, wars — the Great Depression may have been the gravest.

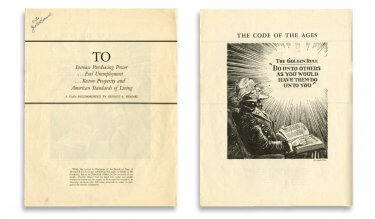

The following excerpt from Hormel’s plan details with remarkable clarity a keen understanding of technology’s potential to improve the lives of all of a company’s stakeholders and a holistic view of what national prosperity really looks like.

“Selfishly unselfish”

If I have twenty-four men doing a certain job, working eight hours a day, and one of them invents a machine to make it possible to do this same work with eighteen men, then six men must become idle because of this labor-saving machine.

Machines produce but do not consume. Prosperity depends on a fine balance between production and consumption. The labor-saving machine disturbs this balance. Production remains at par, but workers’ ability to consume has been lessened twenty-five per cent.

Now, suppose I want to be human, and also selfishly unselfish. Instead of allowing them to join the army of unemployed, I decide these idle men are entitled to a job. So I establish a six-hour day in place of the eight-hour day, and keep all of my original crew at work.

The problem of my crew of twenty-four men is solved. They are all employed at the same pay they received when working eight hours a day. Consequently, buying power has not been disturbed. These men have lost none of their ability to consume my products and those of other manufacturers.

Why will not this same plan apply in every business and solve the nation’s problem?

Sharing Prosperity

Though Henry Ford’s decision in 1914 to double his factory workers’ pay from $2.50 a day to $5 a day has been credited with helping to create the middle class, historians dispute that Ford’s strategy included that outcome. What is undisputed is that Ford made the move as a sweeping — and effective — solution to rampant absenteeism and quality control failures in his plants.

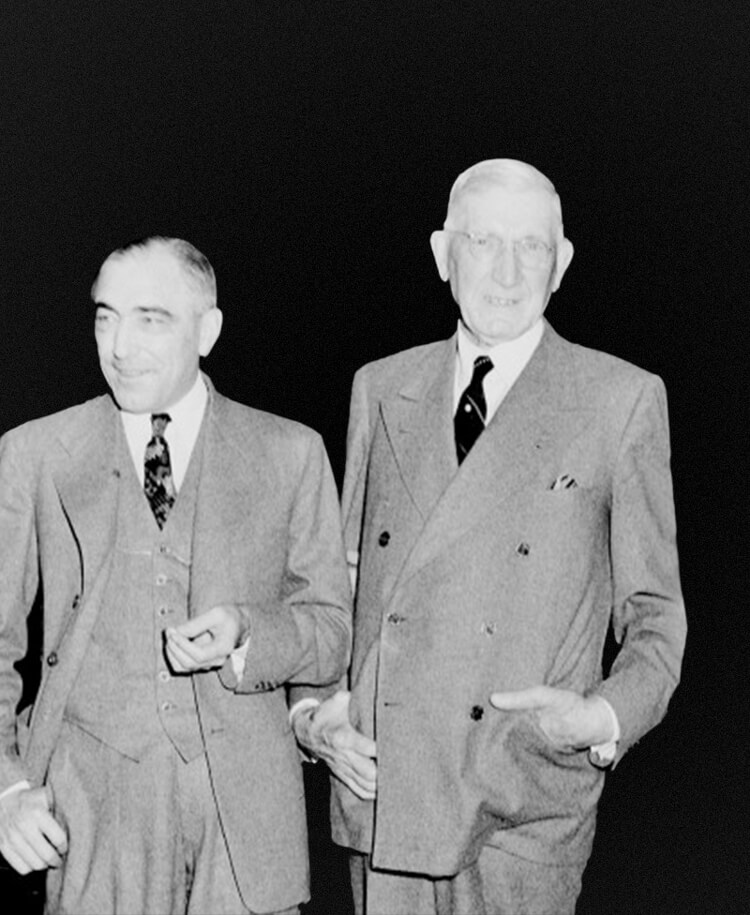

With their plan, George and Jay Hormel took the idea further, explicitly identifying worker spending power and leisure time as key ingredients of a healthy economy. The Hormels knew that in the short term, the extra wages Hormel paid were coming out of their family’s pocket, but they shared a perspective that went far deeper than the bottom line. As the company’s founder, George had spent years performing every job that his employees did, and Jay spent time working in the Austin plants before he took the reins of the company.

George knew the difference between barely making a living and a decent living — a condition he referred to simply as prosperity, and which he and Jay believed should be widespread, not hoarded by a fortunate few. They believed that elevating workers to a situation where they would have the stability, time and resources to enjoy the fruits of their labor was the key to making the whole thing work.

The Los Angeles Times published a series of articles by George on how to apply the Hormel approach to end the Great Depression. Armed with George’s pamphlet, Jay advocated tirelessly for nationwide adoption of the plan. It was controversial in the business community, which was roiled by labor unrest as unions gained power and pushed back against management. In 1937, Fortune Magazine admiringly referred to Jay as “the red capitalist,” underscored by the following passage from a speech he gave to a gathering of Minnesota business leaders:

The idea that an employer is the lord and master of his own business is an antiquated notion. If you are an employer, or if you are the proprietor of a business, you have a job and a trusteeship… It would be asking too much to expect to have a good union unless you also have a good employer… Give labor the fair treatment which is its right, and labor’s right to organize will never harm you.

The same year, Jay personally called President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to point out that the wording of a proposed labor bill circulating in congress would make it impossible for Hormel to continue its annual salary policy. James Roosevelt, FDR’s son and presidential secretary in the mid-1930s, set up the call, which is recounted in the transcript of a 1960 congressional labor law hearing:

Jay C. Hormel … called up President Roosevelt and of course he had known him, and he said “Well, Mr. President, I understand you want me to abolish my guaranteed annual wage plan.”

FDR said, “Why, I certainly do not,” and Mr. Hormel said “Well, you do, you are promoting a bill that would make my plan illegal, and I couldn’t continue it.”

So he explained a little further, and President Roosevelt said to him “You write the language and I will see that it gets into this act.”

And so it did — the Fair Labor Act of 1938 contains a section that still exists in today’s legal code, incorporating Jay and George’s plan, allowing employers to negotiate annual guaranteed pay agreements with employees, providing stability through seasonal ups and downs as well as crises like wars, economic downturns and pandemics.

Today, Hormel Foods continues to focus on the well-being of all of its stakeholders. In August of 2020, the company launched Inspired Pathways, providing mentorship and guidance for navigating the college application process and becoming the first company to pay for the dependents of its employees to attend community college free of charge. In its first year, more than 200 children of Hormel Foods team members applied for the Inspired Pathways program and began the life-changing journey of attending college.

As we navigate the post-pandemic landscape, much of the way we live and work will have to be reimagined. But as history shows, downturns, crises and challenging times are also opportunities for innovation and reinvestment in employees. And while circumstances have changed dramatically, the principles of the company George Hormel started in an abandoned creamery on the bank of the Cedar River still hold.